Another Day at the Office

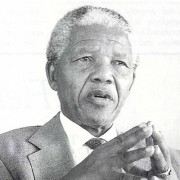

180 days after taking office, South African President Nelson Mandela has charmed the world and is loved by his people. But a nation cannot live on love alone. Now the people must learn to be patient as his new government comes to grips with the vast backlogs created by apartheid. Patience, though, must not be allowed to wear too thin. So, how is his new government shaping up after its first six months in office? Ciaran Ryan reports.

At the age of 76, Nelson Mandela rises at 5:00 am, exercises for half an hour and settles in behind his desk by 6:00 am. The first batch of visitors arrive at 7:30am. He receives them courteously and is always immaculately attired. There follows a dizzying schedule of caucus meetings, State visits by foreign dignitaries and presidential briefings. His office is located at Union Buildings in Pretoria, for 46 years the nerve center of the Afrikaner political dominion. It was here in 1950 that the National Party under Daniel Malan launched the country on the road to international isolation with the promulgation of the Population Registration Act which classified all South Africans according to race and apportioned privilege exclusively to white South Africans. The indignity and hardship this visited on black South Africans is etched on the human conscience as one of the blackest periods of the twentieth century. Each day, as Mandela strides towards his office, the faces of his tormentors, framed in attitudes of imperious forbearance, gaze down at him: JG Strijdom, Hendrik Verwoerd, John Vorster and PW Botha, the architects of apartheid. Then there is the smiling face of FW de Klerk, the former Afrikaner nationalist president who in 1990 released Mandela from prison after 27 years. Now the two men sit beside each other and “drink coffee” in Mandela’s words (he is a teetotaller) while grappling with the problems of administration. It is the stuff of which fairy tales are made. The new government forged by these two men of destiny is a curious mix of ideologies. Erstwhile communists Joe Slovo (housing minister) and Alec Erwin (deputy finance minister) sit alongside General Constand Viljoen, leader of the right-wing Freedom Front party and old-time Nationalists such as Pik Botha (formerly the longest-serving foreign minister in the world, now mineral and energy affairs minister). Former trade union leader Jay Naidoo (now minister without portfolio with responsibility for reconstruction and development), a firebrand who built the South African labor movement into a formidable political force, looks positively taciturn alongside former mining house chief executive Derek Keys, the ongoing minister of finance. South Africa’s communists must be the tamest in the world. Erwin talks of the need for fiscal and monetary discipline in language that would make Milton Friedman proud: government spending needs to be cut, the fiscal deficit must be reined in from its current 6.7 per cent of g domestic product, and productivity needs to improve. Some communist. Says Rand Merchant bank economist Rudolph Gous: “What is astonishing to many Afrikaners is the willingness with which the ANC government embraces fiscal and monetary restraint. But they really have no choice.” Comments economist Edward Osborn: “There is no doubt that the new administration has been saddled with the profligacy of the old. It has precious little latitude to embark on budgetary adventures.” In its last year of power, the National Party ran up debts of $12.3 billion in an attempt to settle the apartheid bill once and for all, while a further $4.1 billion of debts incurred by former nominally “independent” homelands were brought onto South Africa’s balance sheet. Some $2 billion of this debt went to reducing the $8.2 billion deficit in state pension funds in a valedictory vote of thanks to nearly two million public servants, the National Party’s most loyal constituency. The public service is predominantly male, ‘white and Afrikaans-speaking – a high risk group in a job-starved black run South Africa. The National Party secured their jobs by having guarantees written into the interim constitution, but an attrition rate of 8 per cent a year ensures that the public service will be predominantly black within five to 10 years. The new administration wasted little time promoting its own affirmative action programme. Nearly II 000 civil service posts, some offering fantastic salaries, are being advertised. Panic swept through the service and the business sector, and an attempt was made by the Public Servants’ Association to halt the hiring program. The government pointed out the 11 000 jobs were vacant, not new jobs, allaying fears that it was using the public service as an employment warehouse for loyal supporters. Mandela, who once wielded the word “nationalization” as a kind of battering ram, now says the biggest challenges facing the government are economic. The projected economic growth rate of less than three per cent this year is lagging the population growth, while tax levels are too high and foreign investors adopt a wait-and-see stance. “What we require is a growth rate of about 6 per cent,” says Mandela. “I will be happy with that.” In a recent address to the nation, Mandela pledged his administration to fiscal discipline, job creation, economic growth and “a high degree of ethics” – an oblique address, no doubt, to fears that South Africa could become another Nigeria, wracked by corruption and insurrection. There is general agreement that the major economic problems faced by the new government are job creation (46 per cent of the country’s workforce is unemployed) and controlling government spending. The State consumes one-third of all wealth created in South Africa, almost all of it on current expenditure items. The IMF warned that middle income South Africans, who bear the brunt of the tax burden, arc among the highest taxed people in the world. They cannot bear more. Public debt now exceeds $54 billion, nearly half the size of the country’s $1 12 billion gross domestic product, but still shy of the internationally accepted public debt ceiling of 66 per cent of gross domestic product. After education, interest on public debt is the largest single item of spending, accounting for some 17 per cent of the current budget. “The critical issue is not investment from outside, although we need it,” says Mandela. “It is investment from inside the country.”

Fixed investment declined from around 22 per cent of gross domestic product in the 1980s to 16 per cent last year as the National Party government scaled down its spending in strategic projects such as oil-from-coal producer Sasol, off-shore gas company Mossgas and Eskom power stations. The hope is that the ANC’s reconstruction and development program will reverse this downtrend. But apart from pronouncements of intention, the new government has delivered precious little to the millions of poor people who voted the ANC into power on promises of a better life. Of the one million low-cost houses Slovo wants to erect over the next few years to clear the housing backlog, few have been built. “The new government is learning that intentions are one thing, but delivery is much more difficult,” says Osborn. “It needs funding, materials, skills, organization and it will be some time before we see things getting off the ground.” The financial markets have judged the new administration critically. Bond rates shot up 150 points after the election on fears that the new government would continue the National Party tradition of running up debt to fund its administration. “I think the market is bearish on expectations rather than on sound fundamentals,” says Econometrix’s Tony Twine. “So far nothing has really gone horribly wrong – other than a sharp rise in industrial unrest.” The country has been gripped by a wave of strike action as trade unions, many of whose former leaders now sit in government, flex their muscles. The unions argue that democratisation of the country will not be complete until workers receive a living wage. World Bank studies show that South African workers are well paid relative to Pacific Rim countries, but such comparisons appear esoteric to those at the coal face. Many businesspeople question government’s willingness to face a showdown with the trade union movement, which fought the election under the ANC ticket. In which case, industrial unrest could continue well into 1995. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange All-Share index jumped 20 per cent in the six months following the election, running counter to the trend in the bond market. “Companies are coming through with stronger earnings’ growth as commodity prices start to recover,” says market analyst Peter Davey of Frankel Pollak Vinderine. “But a lot of the market’s growth over the last 18 months has come from foreign investors.” Through the financial rand mechanism, which trades at a 20 per cent discount to the commercial rand, foreign investors have pumped $1.1 billion into equities and $514 million into bonds since January 1993. South Africans arc learning that foreign financial investment is a double-edged sword – exiting just as fast as it enters. Foreigners were net sellers of equities in the June quarter to the tune of $314 million (but are starting to trickle back again) while net purchases of gilts are running at around $128 million a quarter. Clearly, foreigners are attracted by yields rather than political statements of intent. Reserve Bank governor Chris Stals says the financial rand is one of the reasons why fixed foreign investment (as opposed to investment in financial markets) is steering clear of South Africa. The financial rand must go, but only when reserves have recovered from their perilously low level of $2 billion (barely sufficient to cover one month’s imports). When the financial rand is abolished, the 20 per cent discount enjoyed by foreigners will disappear. Stals says bond rates will be hiked from 15 per cent to 18 per cent, and the key Bank rate – which the Reserve Bank uses to control commercial bank interest rates from 12 per cent to 14 per cent to compensate foreigners for the loss of the discount. One arm of the reconstruction program which is running according to schedule is electrification. More than 500 000 houses will be connected to the electricity grid this year by the country’s electricity utility, Eskom, which has been rolling out the grid for several years in an effort to bring cheap power to the country’s disadvantaged. Nearly 100000 homes were connected to the grid in June alone. Mandela points to other successes: free medical health care for children under six and pregnant mothers started in June; a school feeding program started in September; and more than $1.2 billion has been made available for reconstruction and development. The ANC’s armed wing, Umkonto we Sizwe, has been merged with the South African Defense Force. A Truth Commission has been appointed to investigate human rights abuses under apartheid and a Tax Commission is looking at spreading the tax burden more equitably. The Constitutional Court will sit early next year and for the first time in its history, the ordinary people of South Africa will be able to challenge the power of the State. Mandela will be judged at the end of his five year term by his success in creating jobs. Most of the 6 million unemployed expect him to make good his promises to provide jobs. The country, by and large, breathed a collective sigh of relief at the passing of the old regime and its tradition of patronage and pandering to vested interests. “It’s a bit early to call the cat a tiger,” says Twine, “but there are signs that the new government is moving in the right direction.”

Ciaran Ryan is a specialist business journalist, based in Johannesburg.

South Africa, The Journal of Trade, Industry and Investment,

Publisher, David Altman

Writer, Ciaran Ryan

Photography, David Goldblatt